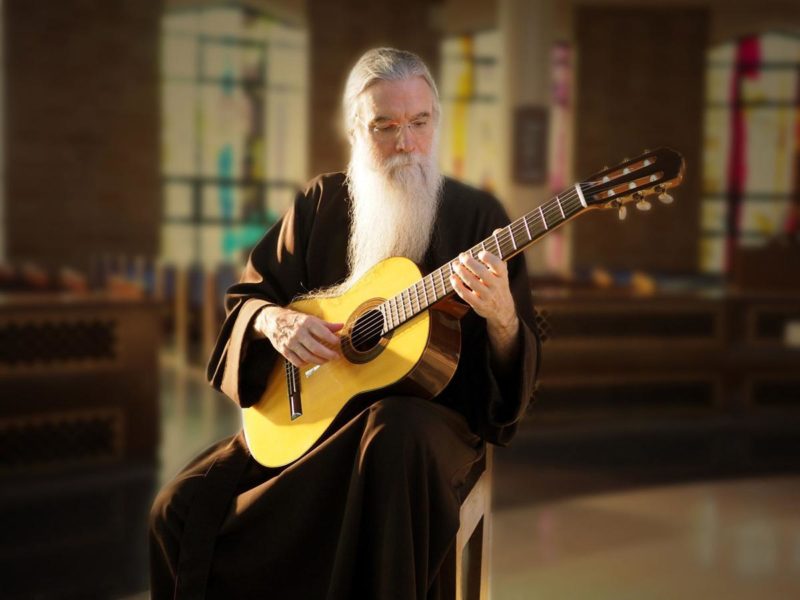

By John Michael Talbot

I had made the decision early in my career to abandon the musical path I had been traveling. Events in my life converged in such a way that I found myself at a crossroads. I was seeking a quieter, more contemplative way of life, a deeper way of experiencing my faith. I just wasn’t satisfied. And the aggressive style of steel-string playing I had become known for was becoming increasingly at odds with where my heart was leading me—a life of simplicity, a life of poverty. And in that, I felt that the Lord was asking me to lay aside my Martin D-35.

It was a very special guitar; I was told that it was originally made for Stephen Stills. He never used it, so it passed to me. I went on to record several of my earlier albums with that guitar: The Talbot Brothers, The Lord’s Supper, and The Painter.

I later found myself out in southern California, working with Keith Green. We got along well, but we also clashed. It was at that time that I felt moved to release the guitar, and so I gave it to Keith as a sort of peace offering for the times we fought. And giving it up became symbolic for me. With it, I was also giving up my past patterns, my aggressions, my violence, my impatience. And in its place, the Lord directed me to play the classical guitar.

Well, I had not played a nylon string guitar since I was ten years old, so this was quite a step of faith for me. I didn’t know how to play it. I didn’t know how to go about buying one. So I ventured down to the music store, and looked around.

For a spiritual person, the choosing of a guitar can be a very spiritual experience. They’re like books—they jump off the shelf and say, “I’m the one for you.” The same thing happens, I believe, with guitars. And that’s exactly what happened that day in the music store in 1978. It was an Alvarez-Yairi—essentially a very nice, handmade copy of a Ramirez. And this one was the top of the line. But it was also marked down to $750. As it turned out, it had a minor flaw, and I ended up getting the guitar for $350.

By this time, I had also moved into a Franciscan retreat center, where I really began my serious search for a more historical Christianity. This guitar was a great companion there. It’s also the guitar that I cut my biggest records with: Come to the Quiet, Troubadour of the Great King, God of Life, and the less popular Light Eternal. Against all odds, these were all major sellers in the Christian contemporary market of the time.

Billy Ray Hearn was running Sparrow Records in those days. He used to call my guitar the “cigar box.” But I loved it, and I traveled with it constantly. And when I traveled by air, it went down below with the rest of the luggage. I didn’t even have a flight case for it. It never occurred to me to take more care, to keep it in the cabin where it would be safe from damage. And sure enough, in its travels it got knocked about. Over and over again. The face would get smashed, and I’d have it repaired. The back would split, and I’d have it repaired again. I even had the neck replaced at one point. And every time I repaired that guitar, it got better. Every time it got knocked in, it got looser. And amazingly, the basses got bigger and deeper, and the brights got brighter.

Finally, in 1991, the folks at Westwood Music in Los Angeles told me that this would be the last time they’d repair it. They’d remake it, but that would be it; I’d have to agree to retire it. No more travels anywhere for this one. I acquiesced, and so now it stays at my hermitage.

I developed a love relationship with that guitar. I named it Brother Juniper, after the possibly fictitious, humble, and thoroughly delightful Franciscan of The Little Flowers of St. Francis. Brother Juniper symbolizes to me the essence of Christian life. Like the Franciscan brother, it’s simple. It’s poor. It doesn’t put on airs. It’s usable. And it can get hurt over and over and over again, but every time it goes through pain, it comes back better, stronger, and more useful.

I also believe that guitars mold to their players. Brother Juniper molded to me in a very special way. There are certain resonances and sympathetic vibrations that result from the way a particular player approaches the instrument. A new instrument hasn’t yet been molded. In the case of a used one, it has been molded to someone else’s style. And it can take months and sometimes years for that guitar to mold to the new player. And as the player goes through changes in his life, the results of those changes will be transmitted to the instrument. I find a wonderful symbol in that, as we are the instruments of God. The more He plays us, the more we are molded and conformed to His image. But it was time to retire Brother Juniper.

Right at that time, a wonderful woman gave to me a Ramirez Centenario, a special model made for their 100th anniversary. I’ve played that guitar ever since. It’s a beautiful guitar. And technically, it sounds better. But Brother Juniper is always going to have a very special place in my heart.

Coming full circle, after Keith Green died tragically in an airplane accident, his wife, Melody, sent the guitar—my old Martin D-35—back to me. And for me, that guitar will always be a symbol of when you give something up out of love, that love gift will always come back to you—but in a way that is totally unexpected and cannot be manipulated. God always gives back whatever we give to Him, and He usually gives back ten, or even a hundred-fold. And it’s always in a way that is beyond what we can expect or imagine.

Visit John Michael Talbot at www.johnmichaeltalbot.com